Published by Al-Monitor on November 21, 2017

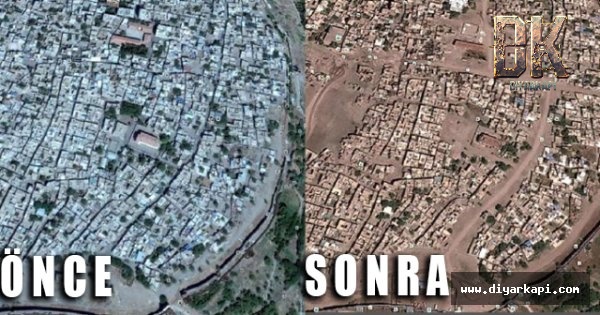

Sur before and after the siege by the Turkish army

“Had the civilization here dated back 70,000 years instead of 7,000, the same thing would have happened,” said Serefhan Aydin, the president of the Chamber of Architects in Diyarbakir. Aydin looked resigned as he gazed around the ancient town that resembled a building site.

Aydin is one of the many locals who lament the brutal urban transformation plan for Diyarbakir’s ancient heart, the area known as Sur, which literally means “fortress walls” in Turkish. The fortress and Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in June 2015. The fortified city was an important cultural center and regional capital during the Hellenistic, Roman, Sassanid and Byzantine times, through the Islamic and Ottoman periods to the present, according to its description on the UNESCO website.

The inscriptions and figures of animals and flowers on Sur’s long walls carry the marks of those different civilizations. Well into the 21st century, the Sur area continued to be a lively neighborhood, with large families living in its two-story houses with courtyards and mulberry trees.

The beginning of the end came in 2015, when Sur became the scene of fighting between the Turkish security forces and the urban arm of the separatist Kurdistan Workers Party. Gun and cannon fire destroyed most of the houses between the city walls.

Six neighborhoods in Diyarbakir are still under curfew, with entry and exit points under tight controls. The curfew is meaningless, as no one lives in the destroyed Sur area anymore. After the clashes, many of the remaining houses in those six neighborhoods have been torn down, this time to transform and reconstruct the area. Some 602 buildings, recognized as historic by the Ministry of Culture, have escaped destruction, but more than 1,000 buildings have been destroyed. For those who have lived in the city for years, the change in those neighborhoods is simply unbelievable. The women who sat in front of the houses to chat and have tea and the children playing in the streets are long gone.

The Turkish government officially started work on its urban transformation plans on Oct. 4, claiming that the town center will be completely transformed in two years.

Turkish officials have long been talking about their urban transformation plans for Sur. In 2016, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said that Sur would become a new Toledo, Spain, and that everyone would be eager to visit its architecture. The remark was met with skepticism among many local organizations and anger from some. Despite the local opposition, the government continued to tear down the old houses after March 2016, when the fighting ceased. The restoration works started a few months later. Finally in early 2017, the plans for the new residences in the neighborhoods were revealed. To the locals’ anger, the designs for the new houses are distinctly different from the traditional architecture of the region.

As the area is on the UNESCO World Heritage List, local pressure groups hoped that the UNESCO officials would step in to stop the plan. But UNESCO remained silent.

“The city of Diyarbakir has hosted one civilization after the other and thus has a multi-layered heritage,” Nevin Soyukaya, an archaeologist and former director of Diyarbakir Museum, told Al-Monitor. “We were the last civilization of this vast heritage. But the destruction of the city has destroyed both the heritage above the ground — the houses, the people who lived there — and the heritage under the soil, which is yet unexplored.”

She went on, “The new buildings have nothing to do with the traditional architecture that we used to see in Diyarbakir. In the new urban plan, we see that the narrow streets of the old town are replaced by large streets. The courtyards, common to our houses, are now surrounded by tall walls, contradicting the traditional sense of neighborliness. This is no new civilization that they are trying to build — it is just an imposition.”

Soyukaya explained, “This renovation and the new urban plans are destroying the city’s tangible and intangible heritage. What they are trying to do will wipe out our collective memory.”

Aydin, the architect, told Al-Monitor, “The new buildings are a mockery — 35% of the life among the city walls is destroyed. When we look at the whole plan from an architectural point of view, the new houses are an insult. The traditional Diyarbakir houses are large, and most have a courtyard with mulberry trees and a basin. What they are building for us are small houses — just a fourth of what the houses used to be. Our narrow streets of hand-cut basalt are to be replaced with asphalt.”

Both Aydin and Soyukaya believe that what’s happening is not simply poor urban planning but the creation of a new identity in the region. “They call the whole thing ‘gentrification,’ pretending that our old houses were unhealthy and primitive and that we would have a better life standard. This is a lie,” said Aydin, adding that the extensive reconstruction is probably profiting some businessman.

Aydin believes that the radical reconstruction also centers on security at the cost of heritage. “Six police stations were built in the city,” he said. “The roads between them are large, unlike the narrow alleys that mark the traditional city plans in Sur. … In 10 years’ time, there will be no more security issues here, but the new urban plans will remain. Once you destroy the urban fabric, there is no turning back.”

is based in Diyarbakir, the central city of Turkey’s mainly Kurdish southeast. A journalist since 1996, he has worked for the mass-circulation daily Sabah, the NTV news channel, Al Jazeera Turk and Agence France-Presse (AFP), covering the many aspects of the Kurdish question, as well as the local economy and women’s and refugee issues. He has frequently reported also from Iraqi Kurdistan. On Twitter: @mahmutbozarslan