Published by The Region on 20/2/2018

Assad and Kurdish forces have negotiated a deal that will allow for Assad loyalists to enter Afrin and battle against the military forces of Turkey, and allied FSA groups. Whereas Russia tried to obstruct such a deal from taking place, it was finalised anyway.

What catalysed it?

Isolation

On January 20th, The Turkish armed forces and affiliated rebel groups operating under the banner of the “Free Syrian Army” began attacking the Kurdish-held enclave of Afrin, a relatively peaceful area in northwest Syria. Prior to the attack, Afrin was under the protection of Russian forces, who withdrew when Turkey and Turkish backed FSA forces launched their attack. Kurdish officials believe that an agreement between Turkey and Russia provided the green light for the attack.

For the people of Afrin, It was never a question of if Turkey would attack the enclave in Northwestern Syria, but only a question of when.

The Democratic Autonomous Administration of Afrin had already engaged in often minor, intermittent clashes with Turkish forces on the border for years. And for the past few months, as Erdogan was warning of a potential “Operation Euphrates Sword” that would aim to expel the Syrian Kurdish PYD group from Afrin, Syrian Kurds began to raise the alarm.

Ankara claims that the Womens’ Protection Units (YPJ), Peoples’ protection Units (YPG) and the Democratic Union Party (PYD) are all a Syrian extension of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which has been waging an insurgency in Turkey for decades. The PYD, which governs the majority Kurdish area of Afrin, claims to be organizationally separate.

Erdogan then, in his words, launched his attack on Afrin to prevent what he calls a “terror corridor” from being formed along the Turkey/Syria border. The YPG forces, on the other hand, have insisted that while they have no intention to attack Turkey, they will defend Afrin with all that they have got. And of course, they reject any insinuation that they are a terror group, a claim only recognised by the Turkish Government.

For weeks now, authorities in Afrin have been demanding protection from NATO’s second largest army.

The International community, has thus far, responded with silence. Aside from a very tame statement of condemnation (which was later retracted) by President Macron of France, the very international coalition which supported the Kurdish Peoples’ Protection Units (YPG), and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in the fight against the so-called Islamic State (IS), did nothing to prevent an escalation of violence.

Neither did the United States nor European countries want to risk their relationship with a NATO member, and whereas the United Kingdom’s Boris Johnson expressed full solidarity with Turkey, Germany continued to maintain its lucrative arms deals with Ankara.

In other words, the U.S, European powers, and Russia did nothing to prevent Turkey and Turkish backed FSA forces to attack Afrin. With nowhere left to go, the International community left Afrin to the mercy of whoever was willing to protect them in this state of existential abandonment.

In such circumstances, why instead of calling for reinforcements, would the Kurds of Afrin ask Assad for help?

Geography and War

Afrin has not only lost moral and material support from its former tactical allies, it has also been kept in a state of geographic isolation in the theatre of the Syrian civil war.

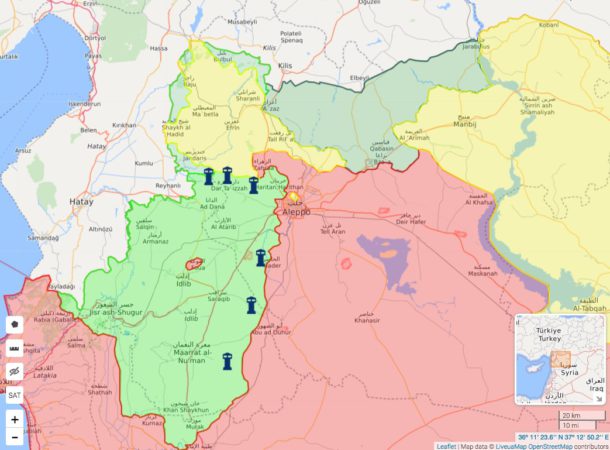

Afrin which lies in the north-west of Syria is surrounded by hostile forces. To the north and west lies the Turkish State. To the south east, Assad loyalists and the Syrian Arab Army are stationed. In the East, Turkish backed FSA forces have been preparing to attack the enclave for years, under the command of Ankara, which insists that the Islamic State and the YPG are two faces of the same coin (nevermind the fact that the latter has sacrificed so much to ensure the defeat of ISIS). And finally, directly south lies the Jihadist stronghold of Idlib, which also has Ankara loyalist group waiting to attack.

In other words, even though the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), of which the YPG is a leading member, controls most of Northern Syria (after having expelled IS), they are unable to send reinforcements because they are blocked by Turkish backed rebels. If they did decide to do so, the reinforcements would have to come through Assad territory.

This state of affairs was constructed with forethought by military officials in Ankara.

In 2016, Erdogan launched Operation Euphrates Shield. Its expressed aim was to attack both the YPJ/YPG and ISIS. In reality, it sought to prevent an advance by the Syrian Democratic Forces from linking Afrin with the rest of territory held by Kurds.

Operation Euphrates Shield was not about defeating IS, it was about ensuring that Afrin would stay geographically distant from the rest of the territory held by Kurdish forces in Northern Syria. Keeping Afrin isolated, in turn, was a way for Erdogan to have leverage over Syrian Kurdish forces.

Turkey has not only backed rebels that hold Euphrates Sheild territory, it has also supported rebels from Idlib, which attack Afrin from the other side. Idlib is virtually under the governance of Jihadist groups. But Turkey has influence over the rebels there as well, which have been enlisted in the battle against Afrin.

The geography of the Syrian battlefield, in other words, has further compelled the YPG to demand that the Syrian government do what it can to prevent Turkey and Turkish backed FSA forces from invading their territory.

What is the relationship between the Syrian Kurds and other groups on the Syrian battlefield?

The Kurdish forces of Syria have mainly gained their territory in their battle against the most immediate threat to the peoples’ of Northern Syria, the so-called Islamic State.

Much of Northern Syria, which was previously held by the Islamic State, is now under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces — a coalition of the Kurdish YPG with other rebel groups in the region. But it wasn’t always like this.

In 2012, Assad repositioned his forces away from Northern Syria in order to fight in the strongholds of the Free Syrian Army. Whereas critics of the PYD have insinuated that this was an agreement between Assad’s government and the Kurds, there is no evidence of such an agreement taking place.

This left a power vacuum in the North. Kurdish forces immediately seized the opportunity to administer control over areas largely inhabited by Kurds. They instituted a system of direct democracy called democratic confederalism and began to demand a decentralized Syria as a path forward for the war-torn country. Areas that fell under their control included Afrin — which was one of the first cities to rise up against Assad — Kobane and Qamishlo.

But then the Islamic State emerged as a coalition of increasingly hard-line former rebels began to radicalize. They attempted to attack Kobane, the capital of the democratic confederalist project.

The Kurds, fighting under the YPG banner, resisted the Islamic State for days.

The United States, feeling that the Kurds could be a reliable partner in the battle against IS, aided in the defence of Kobane.

From then on, the YPG, and an assortment of rebel groups in Syria have been the leading force against IS in Northern Syria. Every territory captured by the YPG was brought under the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, a political body that seeks to forge a decentralized, multi-ethnic polity.

Being in this position has also meant that Syrian Kurdish forces have developed rivalries against the two other warring sides, the decentralized Free Syrian Army brigades and the Syrian Government. Since the beginning of the civil war, the YPG have held a position of neutrality. This has meant that depending on the circumstance, FSA forces and the Syrian government were either harsh foes or tactical allies.

Indeed, this has even translated into deadly clashes with both, over the course of the civil war. In 2014 for example, the YPG entered into a tactical alliance with FSA brigades in the fight against IS, under an operation entitled Euphrates Volcano. Many of those very same groups are now within the Syrian Democratic Forces, a coalition of forces that helped expel IS from Northern Syria, and continue to fight against IS in the province of Deir Ez-Zor. These FSA battalions also constitute the anti-Ankara wing of the Free Syrian Army.

In that very same year, however, the YPG also fought against other battalions of the FSA in Aleppo. Its foes included various FSA outfits like Fatah Halab, Ahrar AlSham, and the Mountain Hawks Brigade.

The same complicated relationship can be seen with the Syrian Government. Take the two months of June and July of 2015 as an emblematic example. In June 2015, the YPG and Syrian government loyalists clashed in the city of Qamishli, according to a report by ARA news. In July 2016, AFP reported that in Hasakah, Syrian Government forces entered into a short-lived tactical alliance to fight encroaching IS forces in Hasakeh

Are Syrian Kurdish forces and the Syrian Government in an alliance? No. But backed into a corner, Kurdish officials felt compelled to make this decision out of desperate circumstances. Just as they did in Hasakah against IS.

Historically, how have Syrian Kurds related to the Syrian Government?

On a brief historical note, Syrian Kurds were often the subjects of some of the most brutal measures taken by the Assad dynasty to forcefully Arabize Syria. In the 1962 census conducted in the province of Jazira, around 120,000 Kurds were stripped of their citizenship. Those that became categorized as foreigners lost property rights, found it difficult to find work, and participate in politics.

In the 1980’s, after the Kurdistan Workers Party’ decided to launch an armed struggle for Kurdish self-determination against the Turkish State, they were given sanctuary by Hafez Assad, who had a dispute over Euphrates water with Ankara. Allowing Kurdish Guerrillas into Syria, however, opened up space for a politicization of Syria’s Kurds, who began to idolize PKK co-founder, Abdullah Ocalan. And whereas it has been commonplace to state, as Amberin Zaman recently has in an NY Times op-ed, that the PKK was also put to use “as a distraction for his own restless Kurdish population.”, this explanation both infantilizes and fails to account for the support that Syria’s Kurds have for Ocalan today.

In fact, despite the tactical and non-confrontational attitude that Ocalan had with Damascus, the PKK constructed a deep affinity between Kurds in Syria and Kurds in Turkey. And it did so by politicizing the Kurdish identity in Syria. This all laid the groundwork for the deep discontent that would begin to simmer after Hafez Al-Assad resolved the water dispute, in return for giving up Ocalan – a decision that would end up with the arrest of the PKK leader, and solitary confinement in Imrali Prison. An unforgivable sin for those who considered themselves followers of Ocalan.

In a Human Rights Watch report, released in 2009 (two years before the Syrian uprising”), interviews with 30 Kurdish activists affiliated with the PYD highlighted not only the discontent that Kurdish activists have had with the Assad Government, but the consequences they faced for advocating for Kurdish rights.

“12 said that security forces tortured them,” the report said, “the most common torture method is beating and kicking on all parts of the body, especially beating on the soles of the feet” the report said.

All of this is to mention that any tactical agreement that has been made with the Syrian Government happened out of circumstances of war, and not, like some of the PYD’s critics seem to insist, due to a secret affinity that the PYD has with the Syrian Government.

So are Syrian Kurdish forces and the Syrian Government allies now?

As of recent, never have relations been worst between the two forces. The agreement for the Syrian Government to enter Afrin and aid in the resistance against the Turkish assault is purely tactical.

In September 2017, representatives in the Assad government began to raise more explicit denunciations against the gains made by Syrian Democratic forces. On the first of September, Assad exclaimed in a speech that territorial claims in Syria were “not up to debate or discussion ever!”, and to underscore his point, he insisted that “the national identity of Syria exists but its essence is Arabism.” Two weeks later, on the 16th of September, Assad aide Bouthaina Shaaban told al Manar TV that the long-term interests of the Syrian Government were to establish control over territory held by Syrian Kurds.

“Whether it’s the Syrian Democratic Forces, or Daesh, or any illegitimate foreign force in the country .. we will fight and work against them so our land is freed completely from any aggressor,” she said.

“I’m not saying this will happen tomorrow .. but this is the strategic intent” she concluded.

In December 2017, Assad summed up the Damascus position to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Olgeovich Rogozin.

“Any who collaborate with a foreign power to fight the Syrian Army are traitors,” Assad said referring to the Kurds of Northern Syria, “It’s as simple as that”.

The PYD, similarly, has also insisted that it would defend its territory from Assad if forced to. In Sheikh Maqsoud, an area governed by Syrian Kurds in Aleppo, Souad Hassan, a senior Kurdish politician said that Al-Assad’s forces would never enter their city.

“We won’t give up Sheikh Maqsoud unless they kill us all” she was quoted as saying by Reuters.

Ilham Ahmad, former co-president of the Syrian Democratic Council, also told Arab tribes in Raqqa that the Syrian government would not be allowed to return to Raqqa either.

“The Syrian regime now has its own efforts and sends letters to our brothers in these areas. They say that they are coming back,” Ahmed told the tribal leaders, “On the contrary, the regime used tanks and planes against our people, bombed their homes and destroyed what they owned. We tell them that you are not fit to return and control our areas”.

Similar statements have also been made about Deir Ez-Zor and Tabqa

Once again, geographically isolated with no material and moral support, Afrin was compelled to cut this deal with the Assad Government.

So what’s next?

What is next is the most important question. If Assad aide Bouthaina Shaaban was telling the truth, and she often does, then the strategic intent of the Assad Government is to retake land from the Syrian Democratic Forces and the YPG.

If that is the case, then what is next could very well be another front in an already complex war, if not a negotiation on unequal terms.

Either way, the future for Afrin is bleak. Had Afrin not been abandoned in the first place, this would have never happened.

To NATO countries, Turkey comes first. To the United States, with IS mostly being defeated, the Kurds are of no use anymore. To Russia, the Syrian Democratic Forces and the YPG ought to be abandoned insofar as they have strong relations with the United States. To the Turkish-backed Syrian opposition, the Kurds are an object of envy and contempt.

Afrin was forced into this predicament because it is alone.

Only negotiations between Kurdish officials and Damascus will prevent this tragedy to get unthinkably worst.